2025 was a wildly interesting year for me. I traveled all over the world working as a photographer and rooted myself deeply in my inner life, community, artistic practice, and career.

One of the most important shifts I’m experiencing is that more and more, I find myself identifying as an artist as opposed to a photographer. Photography remains the most important part of my practice, but not the only medium that defines it.

Instead of sharing a bunch of photos from this year, I decided to put together a short digital zine of my poems called sparkle.

About a year and a half ago, I started writing poems. I don’t know why, I just started writing.

Initially, I saw what I was writing as short stories that resonated in a deeper way when they were formatted less linearly. If you're familiar with my book Close to the Bayou, you'll know that I've been writing in that way for a while.

The line between prose and poetry still feels very vague to me. But after some mental back and forth, it became easier to claim and own that they’re poems. I’m still figuring out what that means to me—to find my poetic voice through writing. I’m enjoying the process, playing with it, trying to take it seriously and equally unseriously. To have fun with it while also exhaling the existential considerations of living and dying—no big deal, right?

I feel vulnerable sharing some of these poems, but one of the most important visions I made for myself in 2025, one I will retain in 2026, is to be fearless. So here I am, the day before New Year’s Eve, fearlessly sharing some intimate parts of my inner dialogue.

I hope there’s a glimmer of resonance in here for you.

Happy New Year!

Billings, Montana

I would say that every year or two, I get to a point in Austin where I itch to leave. My routine starts to feel stagnant. The hustle of happy hours selling natural wine to strangers becomes arduous.

My familiar haunts start feeling a little too familiar. My routine a little too, well, routine.

The other day I finished preparing a mop bucket as I closed the restaurant where I work three days a week. As my coworker walked by, I exclaimed, “One day I’ll mop my last floor, Zoe!”

Without missing a beat, she responded, “I mean, one day you’ll do your last everything.”

Damn. Zoe says some real shit sometimes.

I mopped the floor with a gratitude for being alive, but the fire to leave the city was also still very much there.

I’m typing this from an immovable airport cafe table in Denver. They say there are lizard people who live under this airport. It feels more interesting to believe they do—but in a silly way, not in a Q-Anon conspiratorial way, you know?

To my right is the largest American flag I’ve ever seen in my life, ominously lit and hanging silently above the thousands of travellers shuffling and scurrying to wherever’s next.

For me, where’s next is Billings, Montana.

A few months ago, I was selling my books at an art book fair at the Dallas Contemporary. A stranger approached me and started speaking Mongolian—he was clearly not Mongolian. As we both quickly reached the limit of our language knowledge, we switched to English.

His name was Todd Forsgren. It turned out he had lived in Mongolia on a Fulbright in 2008, the same grant I received to live in Mongolia in 2015. He was photographing gardening and farming projects throughout the country.

Todd was also a vendor at the fair, and I eventually made it to his table to take a look at his work. After flipping through several of his beautiful publications, he started telling me about an artist residency he runs in Billings, where he lives and works as a professor.

It felt like a moment of serendipity. I had been craving the creative space a residency offers as I finish the project I’ve been working on in Mongolia, and here was this Mongolian-speaking man telling me to apply to the one he runs.

So here I am. Seated underneath this gargantuan American flag en route to Billings to spend three weeks focused on writing my next book.

While I certainly won’t finish the book, my goal is to emerge from the residency with three chapters drafted, a better idea of how I want to sequence the images in the book, and a table of contents that will serve as an outline for the project.

Before I left, a friend of mine gave me a notebook to take with me.

Opening its pages for the first time, I found the real gift—a note that finished with the words…

“May you listen to the mountains whispering.”

Here’s to listening.

Valentines

During a prefixed Valentine’s Day service, it struck me that the freshly pulled mozzarella coins vaguely resemble a sliced banana.

I ask the general manager if we have a banana—we make Neopalitan-style pizza and handmade pasta.

Of course we don’t have bananas.

“They have them across the street though.”

During a momentary lull in an unending stream of two top lovebirds,

I make sure my tables are in order and race to the corner store to buy a 79-cent piece of yellow fruit.

Surreptitiously bringing it into the kitchen, I ask one of the line cooks to plate it up just like the mozzarella set.

I don’t know what I was expecting, but it just looked like a sliced banana.

Not at all like the mozzarella coins.

But I still had hope.

At a quick glance and in the frenzy of a chaotic, love-filled service maybe the chef wouldn’t notice.

With his sous chef out sick for most of the week, the man had barely slept in three days.

I just needed him to take one bite.

I imagined the look of confusion, horror, disgust, and then finally understanding that would race across his face in an instant.

I imagined him questioning every mozzarella plate from that point forward.

I wanted him to wonder “Am I about to serve a guest a sliced banana?”

To create chaos in his mind.

To, on some level, make him doubt his own sanity.

I am workplace terrorist.

But if I can’t have a moment like this, then honestly what is there to live for?

I got wrapped up in my excitement.

My plan wasn’t fully considered.

The lighting on the line was too precise.

I revealed my hand a bit.

The coordination between the line cook and myself was unconsidered.

We were doomed from the start.

I hear the cook ask, “Can I get hands on the line?”

Without pause the chef slides from expo onto garmo.

Looking down he sees a sliced banana next to two mozzarella plates—I can see the calculations taking place in his brain.

He hasn’t quite figured out what he’s looking at but he knows something is off.

“Oh my god. What the fuck?! That’s a banana!”

My plan was foiled. He didn’t take the bite.

We all lose ourselves in laughter.

It can be addictive. Especially when you’re walking with close to $600 after a night like that.

After mopping the floors a little after midnight, we head to a French place where it always feels like the staff is either going to fuck, marry, or kill you. The wine buyer, someone I don’t know well but whose air of kind arrogance is something I can appreciate, asks my coworker who worked here for ten years “What do you want to drink?”

A woman with a sophisticated palette, she responds

“Oh, you know me, I’m basic. I like Chardonnay.”

“So you want white Burgundy.”

After finishing an incredible bottle we leave without spending a penny.

As that place closes with time to spare before last call we make a stop at a dive bar known for its BLT and its patrons’ proclivity for cocaine. A moustached man in a red leather vest, matching short shorts, a thick studded belt, angel wings, and full sleeves is belting “Don’t Look Back in Anger” by Oasis as a fog machine fills our throats with whatever fake fog is made of.

It’s a minute before 2AM and the bar staff is yelling at us to “Go the fuck home!”

A coworker reflects that their rudeness is part of the charm. Another remarks

“I provide hospitality all night, they don’t need to be this rude! It’s all industry here.”

The barking continues as I back out of the parking lot making sure not to hit any of the stumbling bodies beginning their journies home.

With all the bars closing simultaneously a feeling of not needing to go home but not being able to stay here, wherever here is,

rumbles through the watering holes that are closing in unison.

A surge of energy fills the city as I hit the highway.

Instead of going home I make my way to my friends’ house—they were one of my first tables earlier in the night.

Seeing the pizza I’d served them several hours ago, I heat a cast iron and start to warm it back up.

The cheese forms a beautiful crisp which makes for the perfect post-midnight snack.

Is it fucked up that I’m eating the pizza I just sold them a few hours ago?

It’s 3:30 in the morning.

In 12 hours I’ll be doing it all over again.

- - -

The beginning of 2025 has been an important reset for me. I’ve been working in restaurants a lot more than I’ve been making pictures which has been an adjustment from last year. While I know it won’t last I’ve been trying, and I think largely succeeding, in seeing the beauty in it.

Working in restaurants can be terrible. It’s an industry with razor-thin profit margins that relies on exploitive labor practices. But that's not what this essay is about.

There’s also something romantic about working in the service industry for an extended period of time. I’ve been working in restaurants of some kind since I was 19 and in some capacity for the majority of the time since moving to Austin in 2018. And while I look forward to the day when this work becomes a decision I make out of personal enjoyment rather than financial necessity, there’s also an earned privilege and a certain magic that you can only access once you become a part of this community.

It’s hard to describe, but this is my shot at it.

Waiting for My Soul to Catch Up | Reflections on 2024

Photo by Dimitri Staszewski

2024 was the most professionally productive of my career.

I made two, month-long trips to Mongolia to follow a story about the spiritual connection nomadic herders have with wild wolves.

I led a group of four tourists to Mongolia on an incredible expedition to learn about eagle hunting and search for a snow leopard.

Workshop Arts published my first photobook Close to the Bayou.

That work was exhibited as a part of the Texas Biennial (up until January 25th in Houston) and PhotoNOLA (up until January 6th in New Orleans).

I pitched and published my favorite editorial story I’ve ever captured for The New York Times about an archaeological dig near San Angelo in Texas.

I started a publishing project, Cedar Fever, and published my first zine under that imprint.

While I’m incredibly proud and grateful to be able to reflect on everything I’ve accomplished in the last twelve months, that production doesn’t come without a certain level of chaos. Over the last few months, I’ve felt an especially strong cognitive dissonance as I’ve been flung across the world into a community of nomadic herders only to be flung back to launch a book about artmaking and dying and then back into that nomadic world to follow a wolf hunt with winter looming.

Less than two months ago I was in western Mongolia, fingertips freezing, kneeling in front of my camera a few feet away from a fully grown wolf under the full moon. The following full moon I found myself in a bar in New Orleans, after a photography festival I was participating in had ended, listening to pirate sea shanties performed by a band of 30 people. A couple of days later I’m waiting tables, describing natural wine to urban cowboys in Austin, and a few days after that, I’m in a driverless car in San Francisco on the way to a fancy dinner party.

It’s a lot to take in.

On a backpacking trip in 2011, someone I was with told me a story about a group of travelers being led through the wilderness by one of their elders. Each day the party would wake up before sunrise, pack up camp, and then hike without stopping until after sunset only to repeat the same process the next day.

One day, the party woke up to see their elder, always the first one up, still in his tent. They waited a bit longer but were anxious to start the day. Someone from the group went to the tent and shook him awake.

“Leader, is everything okay? Shouldn’t we get going?”

“Today we need to rest. We need to wait for our souls to catch up with us.”

I find that when I’m moving so quickly all the time, it becomes harder and harder to slow down. There’s anxiety propelling me to move everything I have going on forward. There’s also an anxiety that comes with the idea of slowing down—a fear that the momentum propelling me forward might not be there after a break.

Maybe that fear is some sort of internalized capitalized ideal, maybe it comes from the industry (or industries) I’m in, maybe it comes from my more direct environment, the people I grew up with, the city I was raised in.

Maybe it’s just me.

A few weeks ago, an old friend told me to “Keep a deep seat and a faraway look.”

I knew exactly what he meant as I read the saying he had texted me, but I wanted to know more about its origins. What I learned, was that while it can be used in a number of scenarios, it’s often said as you’re about to open the chute to ride a bull or a bronco.

On one level it’s a practical piece of advice about how to sit and where to keep your eyes as you ride a horse (or bull).

On another level, it’s a poetic way of saying “Hold the fuck on.”

Or at least that’s my interpretation.

I’ve never ridden a bull and don’t plan to, but the saying was exactly what I needed to hear.

My resolutions for 2025 are simple:

Keep a deep seat and a faraway look.

Give my soul more time to catch up.

Cheers and Happy New Year.

Boots and a Cowboy Hat

I gave another man my boots today.

Wildly bulky.

Black yak leather insulated with sheepskin and felt.

3-centimeter soles to keep your feet as far away from the cold ground as possible.

Boots made to stave off a Mongolian winter.

Boots purchased for a wolf hunt.

Boots that

I would have reveled at pulling out for the singular cold snap we get in Austin each year.

Hulking objects taking up space

and collecting dust the vast majority of the year in a Texas home.

So instead of holding on to this wonderful pair of boots,

I gave another man these boots.

But not just any man.

I gave them to Serikbol Koshegen, or Sekish as everyone calls him.

Someone who, over the last 2 years I’ve spent three full months as his shadow.

It isn’t hyperbole to say that in the last two years, I’ve spent more hours with Sekish than with anyone else in my life.

We’ve ridden horses hundreds of kilometers through waist-deep snow as he and the hunting parties he organized searched for wolves.

I’ve spent countless hours on the back of his motorbike.

We’ve herded animals together in a whiteout blizzard

and watched his horses race across the Altai mountains.

As I gave Sekish my boots, I thought about a time when I was given another man’s hat.

———

After I graduated college a friend of a friend put the idea in my head that I should go work on a dude ranch in Colorado.

That’s exactly what I did.

I got a job as a kids' counselor but quickly started waking up early to help brush and saddle horses with the goal of learning to work as a wrangler.

After a few months, the head wrangler Brandon came to breakfast one morning, a morning where I had slept in, and exclaimed,

“Hey! Dimitri, where were you this morning?”

“Uh, sleeping, why?”

“You’re a wrangler, we expect you in the stables.”

“I guess I’m a wrangler now,” I thought as I tried to play it cool.

I don’t remember if that’s exactly what was said, but the gruff brevity and point of the conversation is what was communicated.

I went to work on that ranch as a 22-year-old from San Francisco who had just finished 4 years of college working in recording studios in New Orleans and New York. While I’d spent time out West, I was not someone who had brushed shoulders with ranchers and farriers before moving to Mancos, Colorado.

One day my coworker Shayna (name changed), someone who grew up in the Western Slope told me “Dimitri, I gotta be honest with you. You need to get some different pants. Those Levi’s make you look gay.”

I had seen Shayna cut a man twice her age down for using the n-word. And while the irony of her homophobic micro-aggression wasn’t lost on me, the 22-year-old version of myself was worried about looking gay on a ranch in rural Colorado.

Shayna took me to the local Big R, a ranch wear store that was unlike any retail space I had ever been in. She helped me pick out some cowboy-cut Wranglers.

As my weeks as a wrangler went on, I couldn’t shake the fact that I was the only one who didn’t wear a cowboy hat. And while I could have just headed back to the Big R to buy one, I already felt like I was playing a part. While my singular pair of Wranglers was fading quickly, there was still a part of me that felt like a fraud.

My coworkers were lifelong riders who kept pistols under their driver's seats.

Men and women who’d sooner walk off the ranch halfway through saddling a horse than be disrespected.

Kids shaped by alpine air and riding bareback at midnight.

A cowboy hat is on one hand a very practical adornment that keeps the sun off your face and neck—something that would have been incredibly helpful under the summer sun of the San Juans.

Sure, it’s just a hat on some level—a tool. But to me, a cowboy hat was like a western crown that I hadn’t earned the right to wear.

I was just some city kid playing cowboy.

After a couple of months of hatless wrangling, a group of high-rolling mule riders came to the ranch.

They pulled up with chromed-out trailers and Alabama moonshine.

We were told to wear our nicest shirts. Before our first ride, Brandon looked at me and said, “You need a hat.”

He headed to his cabin and came back with a well-worn, retired straw hat and handed it to me.

The braided straw had been broken down by the sun and holes had already started to make an appearance on the hat’s crown—hence its retirement.

Putting it on, I couldn’t have been more proud to wear that hat, which I did every day for the rest of my time on the ranch.

———

I originally moved to Colorado to learn to wrangle horses because I was rejected for a grant to live in Mongolia and hadn’t made plans for anything else.

When I moved to Colorado I didn’t even own a camera and becoming a photographer was definitely not something I was thinking about.

After the ranch closed for the season I ended up moving to Wyoming. I worked out there for a bit as I reapplied for the grant to get back to Mongolia. I won the grant the second time around and went on to live in Mongolia for 9 months.

In many ways, I’m glad I was rejected the first time around. My half-year stint at the ranch and time out West prepared me for living in Mongolia and for what I’m doing now. I learned how to ride, really ride. But more importantly, I learned how to engage with a culture that isn’t my own and truly appreciate it. I learned how to observe and listen. I spent time with people whose views of the world were very different from mine, people who I often didn’t agree with on a cellular level, but who I could still bullshit and drink whiskey with around the fire.

I’m not saying that nomadic Kazakhs in western Mongolia are in some way similar to Western ranchers. What I am saying is that continually pushing myself out of my bubble of comfort has exposed me to a world of curiosity.

In over a decade of coming to Mongolia, I’ve seen packs of wolves. I’ve watched a shaman as the ghost of his ancestor entered his body. I’ve seen cascading double rainbows and even the northern lights appear in the viewfinder of my camera.

A couple of weeks ago, as I followed three herders, Sekish, Aibolat, and Jaidik on a wolf hunt, I saw something that in over a decade of coming to Mongolia I had never seen.

I saw three herders rubbing their hands together to get warm.

Needless to say, if Sekish, Aibolat, and Jaidik were cold I was doing everything in my power to forget the pinpricks I was feeling in my fingers and toes and focus on the frames appearing in front of me.

Speaking about wolf hunting, Sekish told me “Not every man can do this. Not every man wants to do this.”

There have been moments in the last few months where I’ve asked myself, “Why do I want to do this?”

Instead of structuring the majority of my decisions around following a wolf hunt, I could be sitting in my house drinking coffee on a more expensive couch than I currently own.

I could be biking around the city in shorts at night instead of freezing my ass off in 7 layers of clothing.

I could be in deep conversation with friends instead of spending weeks at a time without the ability to communicate through language.

But then I think about the fact that I’ve spent the last two years testing my spirit against wolves’.

As the Kazakh proverb I’ve heard and repeated in my head countless times goes,

Wolf says, “I can only be seen by those with the same spirit.

I can only be killed by those with a higher spirit.”

And while this year our hunting party didn’t kill any wolves we saw many.

As Sekish tried my boots on I thought about Brandon’s hat.

As I thought about bringing these fur-lined black leather boots with thick soles home, about wearing them 2-3 times a year, I thought about earning a cowboy hat and questioned if I had earned these boots.

In many ways, I know I have. But if there’s anything I’ve learned living out West and in Mongolia, it’s that cowboy poetry and pragmatism go hand in hand.

More than anything, what I know is that Sekish will wear the boots I gave him until the soles fall off. Hell, if the soles fall off he’ll screw them back on and keep wearing them.

Even if I have tested my spirit with wolves’ and earned the right to wear these boots, I’ll sleep better knowing Sekish’s feet are a little warmer and that those rubber soles are getting ground down a day at a time as opposed to sitting in my garage gathering dust.

Those boots have earned the right to be worn—something I know I won’t be able to give them.

Closing the Circle

I find myself once again sitting in the in-between space of international travel. This time instead of being seated at the bar of an overpriced Turkish airport lounge, I’m stationed on a well-worn seat cushion in the nicest Starbucks I’ve ever seen at Incheon International Airport in Seoul.

The coffee I just bought from an aproned team of baristas is phenomenally terrible—like shockingly bad to the point where I had to take a second sip to fully grasp that coffee could taste so atrocious.

I added some milk and sugar and kept it pushing. I’m not afraid of shitty coffee and this will be one of the last cups I drink for the next five weeks.

I’m on my way back to a community of nomadic herders in western Mongolia to follow and document their spiritual relationship with wild wolves. A week and a half ago I was waiting tables saying things like, “It’s lush and delicate but has more structure than a typical Gamay.”

For those of you who have no idea what that means it’s probably for the best.

A week and a half from now I’ll be capturing the last moments of a fully grown wolf’s life as the family that’s been raising it prepares to slaughter it to use its organs as traditional medicine, its meat as spiritually imbued protein, and its bones as similarly energized tokens to ward off evil spirits.

I can’t figure out which part of my life, the tableside musings on natural wine, a wolf harvest, or my temporal airport existence feel most out of place.

It’s been less than three months since I was last with this community. It doesn’t feel like my mind, body, and spirit have caught up to each other since the last time I was there.

The in-between feeling I get sitting on a 10-hour layover feels like an all too obvious metaphor for the in-between space it feels like I have personally been inhabiting for the last five months—by the end of November I will have spent 10 weeks in an incredibly remote community in western Mongolia and 12 weeks in Austin, Texas where I live.

As I sit here, I hear the familiar sibilance that’s a part of the Mongolian language. I’m getting closer. Pretty soon I’ll be covered in four layers of clothing riding a horse through waist-deep snow in search of a fully-grown wolf.

The night before I left for Mongolia, I found myself at the surprise celebration for two friends who had recently eloped. Without a chance to celebrate their marriage properly, we forced a celebration upon them.

As the dinner went on, I found myself ambling through my packing list in my head. It doesn’t matter how much I travel, I still never learn to pack early. As I grappled with the items I’d need to throw in my bag, I let myself start to think about what I’m about to witness—what I’ll need to capture as a photographer.

Pulled from my thoughts I heard my friend ask, “Are you okay Dimitri?”

I guess I looked more uncomfortable than I realized.

“Yeah, I’m fine. I’m just incredibly anxious. I’ll probably head out pretty soon.”

“What are you so anxious about? Do you still have to pack?”

“Yeah, but it’s more about the story. I only have one chance at this.”

After some more back and forth she finally asked,

“Why are you putting so much pressure on yourself?”

To truly answer that question would have required an intensity I didn’t feel capable of mustering or appropriate for the moment.

Sitting on this increasingly uncomfortable seat cushion that pressure is all I can think about. I feel the intensity in my chest—presenced by the feeling I couldn’t tap into the other night.

I know exactly why I’m putting so much pressure on myself. And while the anxiety of the moment isn’t necessarily comfortable, I wouldn’t have it any other way.

There will only ever be one chance to capture this version of this story.

The pressure I put on myself is the pressure to get it right.

To capture a moment that will only ever happen once.

To do justice to the community that has welcomed me into their world to tell their story.

But the moment I’m hoping to capture isn’t even a specific moment I know exists yet. It’s something I will see in front of me, or maybe I won’t. That’s the fear. That the moment, series of moments, or multitude of moments spread out over the course of a month will pass me by. That I’ll miss the singular moment or the amalgamation of moments that tell the story I’m following.

That it will be right in front of me and it won’t be until later that I realize I missed it.

Or, maybe even worse, that I’ll know an instant after it flashed before my shutter that I was just 1/1000ths of a second too late.

It would be an easy cop-out to say this is something only other photographers could understand, but I think anyone can grasp what I’m talking about.

Think about the times in your life that felt ordinary in the moment, but that you still cling to years later.

The moments that you felt assured would repeat, but never did.

Imagine trying to capture those moments in an image as they are happening.

In some ways that’s an impossible task, but that’s what is so special about truly great photography. It does capture those moments.

My goal is not to take pretty pictures, my goal is to capture imagery that transcends my own ambitions as a photographer—to create images that will continue to transmit something meaningful about the world long after I’m no longer a part of it.

So yeah, that’s a lot of pressure to put on myself.

But if that’s not what I’m after then what the fuck I am doing? Truly.

That’s how I feel.

The real magic of all of this is that of all the moments I have captured for this story, none of them have been promised. When I started this story last spring, before going on our first wolf hunt I met a herder who had spent an entire month hunting every single day. It wasn’t until his last day of hunting consecutively for thirty days that he successfully killed a wolf.

I could see the exhaustion in his weathered face and posture. There was an intensity in his voice as he recounted that month of hunting in the snow.

I feared that after years of thinking about this story, I might not even see a wolf after coming all this way. The herders I’d follow might not successfully hunt and kill one while I was with them. The chances of finding a wolf den were so incredibly slim. These were the elements to the story that I had been thinking about for 8 years before arriving back in western Mongolia for the first time since 2016.

Now, almost two years into this story, everything I had imagined and so much more has manifested in front of my eyes. At every turn, while my imagery is far from perfect, I feel that I’ve been able to capture what has transpired in front of me.

In many ways, it feels like the last two years have culminated in this likely final trip for this story. One in which I don’t have as clear of a vision of what I’m hoping to capture simply because I haven’t had 8 years to think about it—I’ve only had 3 months.

The terrifying part about this trip is that I only have one chance to close the circle. The elements in the story will never again line up so perfectly.

The explosively beautiful part about this final trip is that I actually have this singular chance to close the circle.

Someone told me that anxiety and excitement can feel the same in your body. Depending on the moment it feels like I’m feeling one or the other. It’s probably a mix of both.

My computer just told me the battery is about to die.

I should probably stop writing anyway.

I want to brush my teeth to get the taste of this terrible coffee out of my mouth but the Korean TSA confiscated my quarter tube of toothpaste that was, at one point, over the allowable limit for non-solid substances traveling through the air.

I’ll figure it out.

“Deep rivers run quiet.”

I’m sitting at the bar of an airport lounge that I just paid $199 to get into at the Istanbul Airport. I’ve never been in an airport lounge. The barstool I’m sitting in is unreasonably short for the height of the bar so my computer is almost at my shoulders as it rests on fake marble. Images of Benjamin Netanyahu, a map of the Golan Heights, and b-roll of rocket fire are playing on the TV in front of me. The space bar on my silver Macbook stopped working a couple of days ago so I’m thinking about the appointment I made to get the keyboard fixed as I muscle my way through this paragraph.

This isn’t exactly what I had in mind for my 18-hour layover. I was planning on going into the city, but the mental hurdle of navigating an unfamiliar metropolis after a month in the Mongolian countryside was not something I was up for. I don’t need a drink but I do need to charge my phone and the only outlet that was free in the busy lounge was at the bar. I’m watching my fully outstretched arms make what feels like an acute angle with my face as I continue smashing my keyboard. It weirdly feels like the right thing to do. The space bar is starting to loosen up a bit. Maybe I’ll cancel that appointment.

The only sip of alcohol I’ve had in the last two months was a thimbleful of vodka offered to me by a friend and nomadic herder, Galim, after a horse race—I followed him on several wolf hunts last spring so saying no would have felt rude given that seeing each other again felt like an impossible and beautiful reunion. Last spring he was clean-shaven and weathered by a brutal winter into what had become a deadly spring for his animals. Today you’d never know. It’s a perfect summer day in the middle of a perfect summer. The grass and people’s spirits are high. Galim is wearing a parted, pencil-thin mustache, yellow-lensed sunglasses, and a straw fedora with images of nomadic life sewn into the hat band. He reminds me of someone you’d see on Dollar Day at Golden Gate Fields, a racetrack in Berkeley, California that exists in a universe of its own making where every Sunday during race season it’s “$1 admission, $1 parking, $1 beers, $1 hot dogs, and $1 sodas!” Galim is very comfortable at a horse race. Over the next few weeks, I’d see why as his horses would go on to win over and over again.

Maybe I should get drunk? The beer is free after the price of admission and I’ll be sitting here for twelve hours before sitting on a plane to Houston for another thirteen. After that, I’ll take a taxi to a bus to another taxi to my house. It takes 4 days to get back to Austin from western Mongolia.

A week ago I was wide awake at two in the morning. I spent a few hours making long exposures of a wolf puppy under the Milky Way before the sun started washing away the stars. Sekish, my host, told me he’s raising the wolf to “teach my children what a wolf is.”

You learn a lot about a wolf by spending a few nights together.

Kazakh children are told to wear hats after it gets dark to prevent evil spirits from entering their bodies. I made sure to wear a hat.

What would the guy next to me think if I told him I spent hours, night after night, photographing a wolf puppy, wondering if there were any evil spirits nearby? That doesn’t sound real in an airport full of men in the prickly liminality between being bald and having hair again. The woman next to me has braces and an American accent. She’s on a video call talking about content creation and her personal brand. “Guess who just created a second Snapchat account?!” We have the same computer. I wonder if her keyboard still works.

It feels like I’m in my own liminal space between two worlds. In one world there’s a community that raises wolves. In the other, that sounds like a fairytale.

I’m still processing it all. I haven’t even looked at my photos yet. I need some space from it all.

While I was in the countryside I happened to read Haruki Murakami’s Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World—a book where, without giving it all away, there are two stories, two universes that feel completely separate but somehow connected that slowly swirl into each other. Right now I just feel dizzy.

I know the dizziness will go away. It always does. But the more time I spend asking about wolves…honestly, I don’t even know where the end of that thought goes yet.

On the second page of Hard-Boiled Wonderland Murakami writes that “Deep rivers run quiet.” I can’t get that four-word sentence out of my head nor the fact that it came on page two. What kind of maniac gives you the whole thing right on page two?

I’m not going to get drunk but a beer does sound good.

Cheers.

—

I looked up Golden Gate Fields and it turns out it closed on June 9th.

The Rose Tattoo

The Rose Tattoo was an old bar my good friend and artistic mentor Thomas Mann used to frequent in the late 70s into the early 80s. In April of 1993, Tom walked out of Neville Brother’s show at Tipatina’s at 4 in the morning and saw a “For Sale” sign on The Tattoo across the street. A month later, he bought it for $25,000. Years later, in the early 2000s he moved into the then-decrepit shell of a building and started to transform it into one of the most uniquely beautiful spaces I’ve personally ever been in.

It’s chaotic and considered, which is what I think makes it such a true reflection of Tom.

The Rose Tattoo is an important “character” in my new book Close to the Bayou. It’s a space I thought about a lot as I created that body of work as I supported Tom through his cancer treatment in a different, temporary home he made for himself in Houston where he was receiving treatment. I started writing the following piece while I was staying at the Tattoo a few weeks ago. I was in New Orleans photographing a mind-blowing career retrospective Tom has installed in the space, which to be clear, is his home, studio, and gallery.

I hope you enjoy it. I had a little too much fun writing it.

The Rose Tattoo

To the left of Tom’s toilet, there is, like in most bathrooms, a roll of toilet paper on a circular rod. But unlike in other bathrooms I’ve entered, next to that first roll of toilet paper there is a perplexing arrangement of six additional rolls mounted in varying positions. Four rolls are affixed about a foot above the toilet bowl in a parallel line. Above the fourth roll are another three stacked above it at a 90-degree angle to create an “L” of rolled white, textured paper.

All the rolls are in different stages of use. Some rolls are nearing their end while others have yet to be started.

Over the years I’ve observed these rolls in various stages of their lifespans.

I pull from one of the rolls closest to my left hand and wonder,

Why did I pick this roll and not that roll?

Was it a purely ergonomic decision?

Did something aesthetic attract me to this specific roll?

As I make this observation I realize that the rolls are all different. Some are made from thicker paper, some thinner, and the textures are varied. This means that the rolls are not all from the same stock. They were bought at different times and replaced at different times. I’m already in way too deep.

The first time I stayed in Tom’s home, The Rose Tattoo, was in 2009. And while the bar-turned-home-turned-studio-turned-gallery has always been in a constant state of transformation during that time, the bathroom has largely stayed the same.

These seven rolls have always been there.

Well, I should say that the toilet paper holders have been there that whole time.

But that makes me think, how long has the oldest roll been here?

I have, on occasion, for the novelty of it craned behind my back after relieving myself to pull from the top roll which is in no way conveniently located for this purpose. After brushing my teeth, I’m sure I’ve pulled from a roll less conveniently located near the toilet to wipe the sink. But there are certainly some rolls that I have never touched.

Does anyone ever touch them?

How old is the oldest roll?

I start thinking about the ridiculousness of it all. Thinking about myself thinking about toilet paper holders, the age of toilet paper, and if I’ve used toilet paper from each holder.

Why the fuck would Tom put seven toilet paper holders in his bathroom?

Why the fuck am I taking a shit thinking about this?

Is this art?

It’s 8:07 AM.

—

After writing this I had to ask.

“Tom, why the hell do you have seven toilet paper holders?

“To create a fun little atmosphere. To make people go ‘Oh! This is unusual.’”

Well, it definitely worked dude.

For me, that’s what’s so special about The Rose Tattoo. While the toilet paper holders are a totally ridiculous detail, they are also the perfect detail to illustrate the point I want to make.

Every single corner of Tom’s home has been considered. If you think you’ve considered every corner of your home, stepping into Tom’s home will make you realize just how unconsidered your space is.

Outside his bedroom window, I noticed that he started growing tomatoes in the divet between the two slopes that make up his roof. In an alcove inset almost 20 feet up there’s a Buddha overlooking his office. Nestled in a corner of his jeweler's bench, there’s a row of miniature drawers labeled “INSPIRATION” and “WONDER”.

As I’ve recently started decorating my own home, I consider how much time each of these projects would have taken. Tom is creative and handy, but he’s not a wizard. To get pots and dirt and seeds takes time. To find a Buddha, fabricate a metal frame, climb a 15-foot ladder, and mount it all 20 feet in the air takes time. To collect, arrange, and mount seven toilet paper holders takes time.

My point is that as absurd as the seven toilet paper holders feel, I love that I find myself thinking about the absurdity of it all while I’m going to the bathroom.

In Close to the Bayou I describe the Tattoo as “the largest vessel for and expression of Tom’s creativity.” To me, this building is a living, breathing piece of artwork. For me, entering this space is stimulating and exhausting in the same way that walking through an incredible exhibition is. And while I can’t imagine living there, I always leave feeling totally inspired and energized to create.

In a perfect world, I think some major art collector or museum would buy Tom’s home and preserve it in whatever state he leaves it when he eventually leaves it by choice or as he leaves this world. It’s upsetting that I know that won’t happen. That someone will buy this amazing building and Tom will either have to scurry to figure out what the hell he’s going to do with all this stuff as they make plans to gut it all and turn it into a sterile palace of their own imagination, or worse, some sort of mixed-use nightmare.

I can’t imagine what that process is going to be like. I also don’t have to because I have a feeling that I’ll, begrudgingly but also somehow willingly and enthusiastically get dragged into it.

Until then, it genuinely makes me happy to imagine Tom meandering this space that I’ve seen change so much over the years.

If you’re in New Orleans and have a chance to stop by the Tattoo I’d encourage you to do so. Tom will probably take you on a tour of his 50-year art career that he’s painstakingly curated in his museum-like home. Tell him Dimitri told you to come by.

When you head to the bathroom, where you’ll find numerous pieces of artwork as well, make sure to take a peek at the toilet and maybe even use it so you can ponder which roll you’ll pull from.

Other People's Stories

I remember early on in my journey as a photographer remarking on the seemingly endless waterfall of ideas that many of my favorite photographers seemed to have. I’d think to myself,

“How did they think of that?”

I recognized at that point that most great photography stories are less a reflection of a photographer’s technical skill and much more a reflection of an idea, a spark of creativity, a deeper understanding translated into picture form.

Those sparks just weren’t igniting in me. If I’m being honest, I remember feeling a sort of jealousy. Why weren’t those ideas coming to me?

At the time, I was waiting tables five days a week. As I moved to Austin in 2018 I was looking at a savings account that was nearly empty and while my intention was to work as a photographer I just needed to put my head down and make some money. Before clocking in at 4, I’d be sending emails, applying for grants, making pictures for the local paper, or finding my own stories. It was exhausting.

It wasn’t until I was laid off from my restaurant job in March of 2020 that I realized just how physically and mentally draining that work had been. Tracking my steps on my phone I found that I had been walking 5-6 miles a night in a concrete rectangle for over a year.

As the world slowed down for a bit, my mind was given a moment to pause, to reset, and to feel a real creative spark for the first time since I had moved to Austin. It was during that time that I finished my cookbook Heart-Shaped Tomatoes and started my new photobook Close to the Bayou.

As I was diagnosed with cancer in January of 2022, I was once again forced to slow down as I couldn’t work for nearly six months. During a time when I wasn’t able to make images with any regularity, I was thinking a lot about the images I wanted to make, what I was missing, and what I would focus on once the miraculous liquid that was simultaneously curing this deadly illness and kicking the living shit out of me was out of my body.

As a photographer, I am constantly asked to tell other people’s stories—stories for a brand, a newspaper, a business. That’s what I love doing, telling other people’s stories. But as that miracle liquid left my body and my mind started to *slowly* settle down, I felt a greater sense of urgency to tell the stories that I personally resonate with.

This is not said with any sort of judgment or desire to create a hierarchy of how important different stories are. I say it to acknowledge what I would like to prioritize in my own life and artistic practice.

My mind has shifted to a point where I have the seemingly endless waterfall of ideas that I saw in the photographers I looked up as I was starting out. As I reflect on how far my business has come, I am wildly grateful to say that I also now make the majority of my income from making pictures instead of waiting tables. That has created a dramatic shift in my ability to think creatively. At the same time, for now, my most creative ideas often cost more money than they will make me. To make a living as a photographer I have to look for work that’s outside of that sphere—to tell other people’s stories.

I have always seen the more financially lucrative work that I do propel my next expedition to Mongolia, printing my book, funding an exhibition—these are expensive pursuits. I am really lucky to have found something I care so deeply about that also supports me financially. I also think that at times, that connection can complicate my relationship with photography.

There’s part of me that feels a desire to totally detach the pressure of making money from my work as a photographer.

This is what it feels like to try to make art in a capitalist culture.

I know I’m not alone in what I’m feeling, but it can still feel like a lonely pursuit at times.

As 2023 comes to an end, the existential question I’m asking myself is if making money from photography is even something I care to engage in?

And while I know the answer has to be “yes” in some ways, how can I do more to use my photography to foster connection and create more joy in my own life? Ultimately that’s what I care about.

What I really care about doing with my photography is very specific—documenting a wolf hunting tradition in Mongolia, creating a new body of work about extreme heat in Texas, telling a story about the expansion of I-35 and the displacement of minority-owned businesses.

The list of ideas that I have is long. It can feel like I don’t have enough time to do them all while also making enough money to pay my bills. My days are often consumed writing emails that start with “I’d be excited to introduce myself and my work!”

What I am truly excited about is living with a nomadic family for weeks at a time. I am excited about using the book form as an artistic medium. I am excited to actually make work. My work.

If anyone is still with me as I deteriorate into existential word vomit, here are my photo-related goals for 2024—I have some other personal goals but those are just for me. If you see me, hold me to them.

Do more popups.

Engaging with your community in person fills you up! Do more of that dude!

Print more images.

Instagram is dumb. Websites are dumb. Ink on paper is cool.

*as he posts this on his website and Instagram*

Make more books that will go in people’s homes.

See above.

Exhibit my work in some way, even if it’s in my garage.

Push yourself to exhibit your work in ways that resonate with you. You don’t need expensive frames and a white-walled exhibition space to make this happen!

Make more connections in person instead of online.

Send fewer emails. Meet people, shake their hands, look them in the eye.

Get back to Mongolia.

Riding horses across frozen rivers and looking through binoculars at tiny wolves is the literal dream. 12-year-old Dimitri would have expected nothing less. Do it for him.

“ Il momento è arrivato.”

During the second week in January, my family was given the news that my grandmother Elda Cristini’s kidneys were functioning well below the levels that indicate “End Stage” kidney failure. And while the doctor gave her two weeks to live, they said that really, “She shouldn’t be alive.”

Frankly, I don’t think it’s possible to sugarcoat anything from someone who lived in a time when acquiring sugar was illegal. Even before she got the truth that she demanded, I think my grandmother recognized that she was transitioning into death.

It took a few days in a hospital bed but in a brief moment of universal understanding, I watched an expression I had never seen flash across my grandmother's face. It was a brief smirk that I’ll never forget. It was like watching a cat well beyond her nine lives realizing that she’s at the end of her last, a prolific bank robber in the midst of a heist realizing that finally, they were going to be caught. It was an expression of relief and grief, of graceful acceptance, but also a will to fight for just a little bit longer.

It felt like her spirit shining through.

Speaking to herself, but maybe also to her own anchors–God, Padre Pio, her mother, I watched and listened to her say in Italian “Il momento è arrivato.”

The moment has arrived.

In what shouldn’t come as a surprise, Elda would go on to live until April 30th, well beyond the two weeks her doctors gave her. While she may have acknowledged that the transition had begun, she wasn't ready to go right away. Over the last few months, my family and her closest friends were able to continue to create many beautiful and lasting memories.

The night before her passing, Elda sat at her kitchen table with my mother making zucchine alla parmigiana.

Today would have been Elda’s 103rd birthday.

* * *

I could say a lot more. Maybe, in time, I will.

What I do want to express now is how grateful I am to everyone who helped preserve, share, and elevate my grandmother’s spirit through Heart-Shaped Tomatoes, most notably my mom Maria Cristini, the book’s co-author Madelyn Wigle, and the book’s designer Mitch Wiesen.

I also want to thank everyone who has purchased a copy of Heart-Shaped Tomatoes and more importantly who read my grandmother’s stories and recipes and made them their own. It's an honor to know that her story resonated with so many people and that her legacy will be carried on through the hearts, minds, and bellies of so many people she never met.

My grandmother passed knowing that hundreds of people from all over the United States, and even a few abroad, have made her recipes! At the moment I only have about 25% of the copies of Heart-Shaped Tomatoes that I started with. Realistically, I don’t see myself continuing to promote this book in the same way that I was able to before. If you feel inclined to purchase another copy for a friend, I would genuinely appreciate it. I look forward to sending this project off together with my grandmother.

Smoke and Spirits

The real revelation that I’m heading back to Mongolia always hits me as I arrive at my gate at Incheon Airport. The global nature of the travelers passing through Seoul immediately narrows. Rounding the corner to my gate I’m greeted by the familiar sibilance that’s characteristic of the Mongolian language. It’s a language that, like so many aspects of the country, can feel harsh at first.

Read MoreHeart-Shaped Tomatoes at Nixta Taqueria

This past Sunday, I had the honor of collaborating with Chef Edgar Rico of Nixta Taqueria who reinterpreted several of my grandmother Elda Cristini’s recipes from my cookbook Heart-Shaped Tomatoes.

For those unfamiliar with Nixta, it’s a restaurant on East 12th Street in Austin, Texas. Since opening three years ago, Nixta and its chef-owner Edgar Rico, and owner Sara Mardanbigi have consistently been awarded for the incredible food they put out. Most recently, Chef Rico won the James Beard Award for Emerging Chef and was named to TIME Magazine’s TIME100—a list of the world’s most influential artists, leaders, and innovators.

I’ve been lucky to work at Nixta off and on for the last year, and it has been through that work that I’ve come to know Edgar and Sara, who are married and co-own Nixta together. They are two of the kindest and most genuine people I’ve ever met and certainly worked with.

I was taken aback when during a quiet moment at the beginning of a shift Edgar asked me very casually, “Would you be down to let me cook some of your grandma’s dishes for a dinner here?” My answer was a much less casual, and much more emphatic “Hell yes!”

It took a while for our schedules to match up, but as they finally did I was nervous and excited about the opportunity to have my grandmother’s recipes shared and manifested in an evening of celebration.

I tried to capture the whole process of what went into the dinner. For me, the experience of watching Edgar, Sara, and both the front and back-of-house teams prepare the food was as important to me as seeing guests excited about Edgar’s interpretations of my grandmother’s recipes.

It was amazing to see the haphazard coordination of three pairs of arms twirling together 26 plates of spaghetti with my grandma’s pesto recipe. And for that pesto pasta to be so thoughtfully paired with wine from Abruzzo, the region of Italy where my grandmother is from.

As I watched those 26 plates come together, I thought about my grandmother’s culinary energy, her old-world stubbornness, her spirit twirling into that spaghetti, onto the plate, and into the mouths and bellies of a group of friends and strangers who have never met her before.

It was beautifully overwhelming. A moment and an evening I will remember for a long time.

✷ ✷ ✷

In addition to everyone at Nixta, this dinner would have never happened without everyone else who contributed to making Heart-Shaped Tomatoes—specifically the book’s co-author Madelyn Wigle, my mom Maria Cristini who wrote all the recipes, and the book’s designer Mitch Wiesen.

Click images to enlarge.

Summer in 19 Images

Between June and August, I spent five weeks teaching and capturing marketing imagery for Smithsonian Student Travel and Putney Student Travel followed by two weeks of travel with my partner. It has been an incredible summer filled with so many opportunities to find and capture interesting imagery. As I’ve started to look through the thousands of images that I captured, I wanted to share a small selection here on my blog.

While the goal of most of my images this summer was very specific—to tell the story of students traveling abroad in a way that will help sell programs, in the moments between capturing that exciting client work, I was able to find moments to shoot for myself.

What I love most about traveling is the opportunity to let go of some of the rigidity that comes with existing and photographing in a more familiar environment. As I’ve been going through my images, I see myself shooting with much more fluidity which is something that I hope to incorporate into my practice more broadly.

Over the last year, I’ve been learning and studying the art of pairing and sequencing images. As an extension of that study, bookmaking has become an essential part of my practice. And while this blog and a book certainly aren’t the same formats, I wanted to use this collection of images as an opportunity to practice pairing and sequencing images.

My hope is that these images tell a story of sorts, but more importantly, evoke the way traveling throughout Europe this summer made me feel. A brush with the unfamiliar, mass tourism, and awe-inspiring beauty all together all at once. Take a look!

My students taking a moment to themselves after a morning exploring St. Peter's Basilica within Vatican City during a program with Smithsonian Student Travel.

“How did this person afford this trip to Europe?” Month

I saw a Tweet the other day that said “It’s ‘How did this person afford this trip to Europe?’ month on Instagram.”

It was hilarious, I felt personally attacked in the best way, and it also got me thinking about my own presence on social media—something I already think about regularly as a photographer.

Over the last five weeks, I’ve been photographing programs for Putney Student Travel and Smithsonian Student Travel as well as leading a Smithsonian program throughout Greece and Italy. I’ve been sharing some of what I’ve been experiencing on Instagram, but ultimately I recognize that what I share is only a narrow sliver of my overall experience.

To put it simply, I can’t afford this “trip”, I’m working. I haven’t had a day off in over thirty days at a time when I’m still recovering from chemotherapy treatment which ended just a few months ago. If you’ve never led a group of high school students internationally, it’s difficult to articulate how all-consuming this type of work becomes.

What you will not see on social media are the back-to-back 18-hour days, the lost luggage, the logging of receipts, the calls to the office, and the questions which become mantras—“Dimitri, where’s the bathroom?” in a space as foreign to me as it is to them and “Can you put your phone away?” just everywhere, all the time.

I want to share this because if I’m going to be part of the mass of people throwing shallow positivity into the world, I at least want to think critically about it and encourage conversation. And to reveal some of what is being left out. I want to be honest about the fact that as rewarding, fulfilling, and beautiful as this summer has been for me, it has been equally challenging and exhausting.

In typing this I also feel the need to acknowledge the place of privilege that I’m coming from. As exhausted as I might be, it’s still an immense privilege to be traveling in luxury to the places I’ve been to over the last five weeks. Even though I am working, I’m part of a very small percentage of the globe that has the opportunity to travel like this. My privilege is not lost on me and my gratitude for the experiences I’m having is something I actively express inwardly and outwardly.

At the same time, while seeing beautiful monuments and sunsets is visually enthralling and awe-inspiring, the most important aspects of my job this summer cannot be shared on social media.

As a teacher, I have the opportunity to actively affirm identities, create space for young people to feel safe as they express their truest selves, push students out of their comfort zones, and help expand the minds of high schoolers. Creating those environments and moments is not easy. It requires empathy, intentionality, and time. As I’m doing this work I feel the importance of what I’m doing, which is what makes it so rewarding.

This is all to say that I’m incredibly grateful for the last five weeks, but it certainly hasn’t been a vacation. Social media is weird and I don’t think we can change that. I think it’s important to be honest and reflect on what we are and aren’t sharing to remind ourselves and each other of the inaccurate reflections of reality that we are all constantly putting into the world. This is my small attempt at doing that.

- - -

I’ll finish this blog post by saying that if after reading this you feel like teaching international photography workshops to high schoolers is something that you’d be interested in or potentially interested in, you should reach out! I’d be happy to share some more info. The company I work for is always hiring each summer and I know they take recommendations to heart.

Hiring doesn’t happen until early next year, but shoot me an email, text, DM, whatever now so I can keep you in mind as hiring comes around.

Turning 102

On May 18th my grandma Elda Cristini turned 102. I’ve been lucky to spend a lot of time with her over the last year, but this birthday felt special as I recently beat a cancer diagnosis, and she a nasty Covid infection. There was a lot to celebrate together as it was also the first time I had been able to see her in person since she had received the finished version of Heart-Shaped Tomatoes, the cookbook I wrote about her.

To mark the occasion, I decided to interview Elda and ask her about cooking and what it means to her. As always, she didn’t disappoint.

I thought about including subtitles but decided not to. I love the way my grandma speaks English and feel like her grasp of the language never fails to allow her to get her point across if you’re listening closely. So listen closely! I think she has some beautiful thoughts to share.

My good friend Andrew Meriwether, an incredibly talented audio producer, created the script. Here’s a link to his website.

Heart-Shaped Tomatoes © Dimitri Staszewski and Madelyn Wigle

Being Tom and "Twenty Twenty Too"

During the summer of 2020, I received an email from a friend and uncle-figure Thomas Mann with the subject line “Ketch-up.”

He shared that he had been diagnosed with stage 3 prostate cancer and that he would be undergoing treatment from January through March of 2021 at MD Anderson in Houston. While he would be receiving some of the best treatment available, it would be an intense medical journey.

Tom has been an important figure in my life since I was a baby. I apprenticed with him as a jeweler when I was 16 and when I moved to New Orleans for college in 2010, he became an even more central figure in my life. He has been an artistic mentor since I was a child so when he asked for some help setting up his space in Houston and working on some jewelry projects, I wanted to help. At the time, I was working for the Texas Senate, which required daily Covid testing and the office I was working for was incredibly Covid cautious. There aren’t many moments in life where we’re asked to help a friend or family member in that way, and I was lucky to be in a position to safely help Tom.

From January through March, I decided to drive to Houston each weekend to make jewelry with Tom and photograph his experience of going through cancer treatment. This was during the height of the pandemic before vaccines were readily available so most weeks, I would be the only person Tom would engage with face to face outside of his care team.

But what initially started as an opportunity to help a friend turned into an artistically transformative experience for both of us.

I’d arrive at Tom’s every weekend, usually to a mountain of dishes, scattered to-do lists, and a joyous “Honey! I’m hoooome!” from Tom as he’d come in after his final treatment of the week. After I’d cleaned the kitchen, we’d cook up the most extravagant meal we could muster and then sit with each other and talk about what was on our minds—which was usually quite a bit during the first quarter of 2021!

I look forward to sharing more about this work in the coming months. I’ve been keeping this project to myself for almost a year at this point and I’m really excited to finally be sharing it.

Here’s a wider selection of the work. Feel free to reach out to let me know what you think!

✷ ✷ ✷

Wearing the necklace my dad made me as my mom cuts my hair after my first round of chemotherapy.

In a twist of fate, on January 4th as the “When you realize 2022 is pronounced Twenty Twenty Too” memes were still piping hot, and six weeks before my 30th birthday, I was diagnosed with testicular cancer. It has been a strange experience going from focusing on creating an intimate body of work about someone else’s experience with cancer to going through treatment myself. I’ve been forced to relearn lessons I thought I had learned through Tom’s journey.

As I’ve undergone surgery followed by chemotherapy, Being Tom has taken on even more significance for me personally which is why I’m choosing to share it now.

I’m happy to say that chemotherapy is very effective at targeting my specific cancer, which is highly curable at the stage I caught it at. I recently finished my third of four rounds of chemo. While treatment has certainly been challenging, the light at the end of the tunnel is the incredible life I get to continue living.

I’m so lucky to be surrounded by such a supportive group of friends, my girlfriend Kendall, and my mom Maria who have all been with me every step of the way in Austin. I’m also exceptionally grateful for the friends and family who check in on me every day from outside of Texas.

As I make this final push to what I hope and expect to be the end of my treatment, it gives me the opportunity to reflect on the things that I’m grateful for.

I’m so lucky to make a living from what I’m most passionate about and deeply appreciate everyone who has been following my work, especially over the last year. I feel very creatively energized but haven’t been able to create as much as I would have wanted to since January. I’m excited for that energy to push me forward. More to come soon!

2021 in 21 Images (with some videos!)

As is always the case, it’s impossible to distill any year into a selection of images. And while summarizing in this way cannot possibly reflect all the year’s nuances, I find it to be a really helpful exercise for my own photography practice. It gives me the opportunity to ask myself how I was using photography for the last twelve months.

That reflection has come to reveal some often unconscious connections between the various projects I’ve been engaged in. Looking back at my images from two years ago in 2020 for example, it was clear that I was using photography to try and make sense of the world outside of myself.

Looking back at my images from 2021, I see myself looking inward. I was able to use photography to deepen my relationships with those closest to me and as an excuse for introduction. I even photographed myself formally for the first time!

I consider myself a documentary photographer, but that term can mean so many things. As opposed to being a more detached observer, I found that in 2021, photography became a point of engagement—it helped enrich my experiences, brought me closer to the people I was photographing, and helped create new layers of meaning in my life.

As a photographer, I have so many people to be grateful for in 2021. I’m grateful for the friends, family, and strangers who graciously allowed me to capture their images. I’m grateful to the clients who hired me. You all allow me to make a living doing what I love. I’m especially grateful to everyone who pre-ordered a copy of my cookbook project Heart-Shaped Tomatoes. I feel incredibly supported and lucky to be doing what I’m doing.

Take your time going through the twenty-one images and videos that I chose to represent this year. You can click on the images to enlarge them.

I was setting up my camera when Houston-based rapper WxxdyB hopped out of his car and asked “Do you shoot videos?!” I told him I mainly shoot photos and asked if I could take his portrait.

My grandmother Elda Cristini the day after her 101st birthday in Belmont, Massachusetts.

Thomas Mann, from the series Being Tom.

Contemporary beading artist and Big Chief of the Young Seminole Hunters Demond Melancon at his studio in New Orleans, Louisiana.

For me, 2021 began as I put on a suit and went to work for the Texas Senate five days a week and spent weekends driving to Houston to help a friend and chosen uncle through prostate cancer treatment.

My job with the Senate was admittedly very challenging. I was often in the room as bills that I believe violate our constitutionally mandated civil rights were being passed. I’m very comfortable documenting history as a photojournalist serving the public. But documenting history as a service to the Texas Senate was not something I was comfortable with long-term. While I worked for the non-partisan Senate Media Department, I felt that in a small way I was aiding the process of passing the legislation I was fundamentally opposed to. Naturally, there was a lot of introspection.

As a photographer, I often think about the moments I’ve missed—photos I regret not taking. As a bill I was fundamentally opposed to was passed in the Senate, its author called on me to capture a moment of triumph. Without thinking much about it, I stepped into my role as a photographer, took the picture, and left for the day. Coming back to work the next morning, I went through my images from the previous day. I was fixated on that series of images. I realized that for the first time, I regretted taking a photo.

The image was unremarkable, and there’s no need to share it here. But it was an important moment for my progression as a photographer.

Have you ever regretted taking a photo?

While I working for the Texas Senate, I would leave Austin each Friday right after work and drive to Houston where I was helping an artistic mentor and uncle figure of mine, Thomas Mann. Tom was undergoing prostate cancer treatment at MD Anderson and needed help making jewelry, but also just appreciated the company as his ability to interact with other people was basically non-existent because of Covid. I was getting tested six times per week because of my job and taking extreme precautions not to get Covid, so I felt comfortable visiting Tom.

My experience with Tom turned into something I never could have imagined. We’d cook and make jewelry together during the day, and spend hours just sitting and talking with each other at night. I had some of the most influential conversations of my life during the three months I spent with Tom—conversations that shifted how I see myself as an artist and what I’m doing as a photographer.

I ended up creating a large body of work about Tom that is broadly about his experience of sickness in isolation. Below are a few images from the project. I’m excited to share more about that project as soon as possible!

By May of 2021, I was completely burnt out. I had almost no time to myself between January and May and while that period of time was one of the most artistically and personally fulfilling moments of my life, I needed a break from everything and everyone.

Towards the end of my contract with the Texas Senate, I was offered another contract to teach a photography workshop in Yellowstone National Park. I jumped at the opportunity which gave me the perfect excuse to plan a five-week road trip from Austin to Montana and back. I spent a lot of time looking for stories and creating more photography work, and just as much time camping on mountain tops and soaking in remote hot springs.

Monument Valley in the Navajo Nation.

Waking up to photograph the Bonneville Salt Flats at sunrise, I stumbled across an interesting scene as I was heading back to the interstate. I would come to find out that I had just entered the second largest amateur rocket launching event in the country—LDRS 39, which of course stands for Large Dangerous Rocket Ships. It’s the Tripoli Rocket Association’s premier event each year and was hosted by the Utah Rocket Club this time around. I spent a couple of hours watching rockets explode into the desert air and making pictures of this passionate group of enthusiasts.

“Everybody wants to be a tooler. They wanna make saddles, they wanna make pretty stuff. They don’t wanna get their hands dirty.”

“Religion is man’s interpretation of what God has to say…I consider myself a man of God who rarely succeeds at being a man of god.”

Dallas at the Majestic Dude Ranch in Mancos, Colorado.

During the last quarter of 2021 I needed to focus less on creating new personal work and more on finalizing my cookbook project Heart-Shaped Tomatoes while balancing some exciting freelance projects. Heart-Shaped Tomatoes was co-authored by Madelyn Wigle with recipes by Elda Cristini and Maria Cristini. I can finally say that the book is finished! It has been printed and is currently on a boat from South Korea to the United States. Global supply chain issues have delayed the delivery of the book, but it’ll be here soon!

One of my favorite freelance projects of the year was creating these short videos for GoDaddy Studio, a new app that GoDaddy acquired. After paying for a subscription, users can use stock video content on their own social media. I tried to create videos that could exist beautifully on their own even before users overlay their own logos, text, etc. It had been a while since I had shot any video, but getting back into it has given me energy to reincorporate it into what I’m doing personally and professionally.

My girlfriend Kendall Narde was an amazing model for this shoot.

As I look forward, I’m excited to finally be able to deliver Heart-Shaped Tomatoes to the hundreds of people who have already pre-ordered the book. I have some more work to do to finalize my project Being Tom and look forward to sharing that work soon as well.

Self-portrait taken at my grandma’s house the day after her 101st birthday.

Sunrise at Monument Valley on the Navajo Nation in northern Arizona.

Five Weeks Out West

After almost five weeks of driving, teaching, soaking in hot springs, long and short hikes, and lots of image-making, I woke up at 5 am to drive to the northern edge of the Navajo Nation in Arizona to watch the sunrise in Monument Valley.

Like so many parts of this trip, it was a moment that I had always envisioned growing up as an American who has seen images of these buttes my whole life.

As I composed an image of the iconic landscape, a wild dog (common in the Navajo Nation) wandered through my shot and situated itself perfectly to watch the sunrise with me. As we were watching together, a crow joined us for this moment. I'm deeply impacted by moments like this. And like I said in my last newsletter, they seem to happen more frequently for me out West.

To feel connected to the landscapes I'm traveling in is ultimately the biggest gift of being on the road.

I hope you enjoy a few of my favorite images from the past five weeks.

Click on the images to enlarge them.

The Colorado River in the Dirty Devil Wilderness southern Utah.

Horses at the Majestic Dude Ranch in Mancos, Colorado.

Slot canyons near Escalante, Utah.

Glacier National Park

White Sands National Park

Byron Seeley in Jeffery City, Wyoming

Jeffery City was a uranium boomtown now home to an official population of fifty-eight according to the 2010 census. Bryon Seeley, whose bright blue eyes and sun-worn skin match the distinctive glaze and weathered texture that characterizes his pottery, is one of those fifty-eight people.

Driving north of Rawlins along U.S. Route 287 for the first time in five years, I was overjoyed as I passed through Jeffery City to see the familiar hand-painted lettering for Monk King Bird Pottery.

“You look familiar. Have you been in here before?” It was an unexpected welcome that meant more than he knew.

“I’ve been here fifteen years.” After a long pause he continued “If you count the first nine years where I was drinking. I’m four years sober.”

Quickly moving past his questionable math, I fixated on the word “sober.”

I lived in Lander off and on between 2014 and 2016. During that time, Bryon, whose last name I didn’t know at the time, was a familiar character in the small Central Wyoming town of just over seven thousand people. I say this in the most affectionate way possible, but at the time I knew Byron as the town drunk. I certainly didn’t know Byron well, but everyone who spent any time drinking in Lander knew of him.

“[20]17 was the solar eclipse year and I was on my way out...I wasn’t trying to drink myself to death, I just didn’t care if I did.”

Byron says that after waking up in the hospital “I realized I didn’t want to die after all.”

He describes his journey to sobriety in slow, short sentences, “It’s hard. I loved alcohol. It was fun. My life’s a lot better.”

Today Byron’s pottery business is doing better than he ever could have imagined. He’s selling his work faster than he can make it, and yet he’s still running his business on his own terms.

After picking out a beautiful mug and bowl, I realized I didn’t have enough cash for both. Byron told me not to worry—to take the bowl and send the $12 I owed him to his P.O. box in Lander.

As I left he said “Say hello to Lander for me.” He rarely goes into town anymore and when he does it’s only to help take care of his mother.

I had been apprehensive about going back to Lander and many of the places I’ve visited in the last month. Not because things ended badly, but because they ended so perfectly. I didn’t want to complicate the golden memories I had of some of the places I was returning to. And yet, I had planned to come back and inevitably complicate those memories.

But reconnecting with Byron was incredibly impactful. It was the kind of magically serendipitous interaction that seems to happen for me frequently when I’m out West.

As I’ve returned to familiar spaces and reconnected with people from my past, it’s easy to remember them as they were. But we’re all changing, shifting, progressing, regressing, and evolving.

The town drunk got sober and doesn’t go into town anymore.

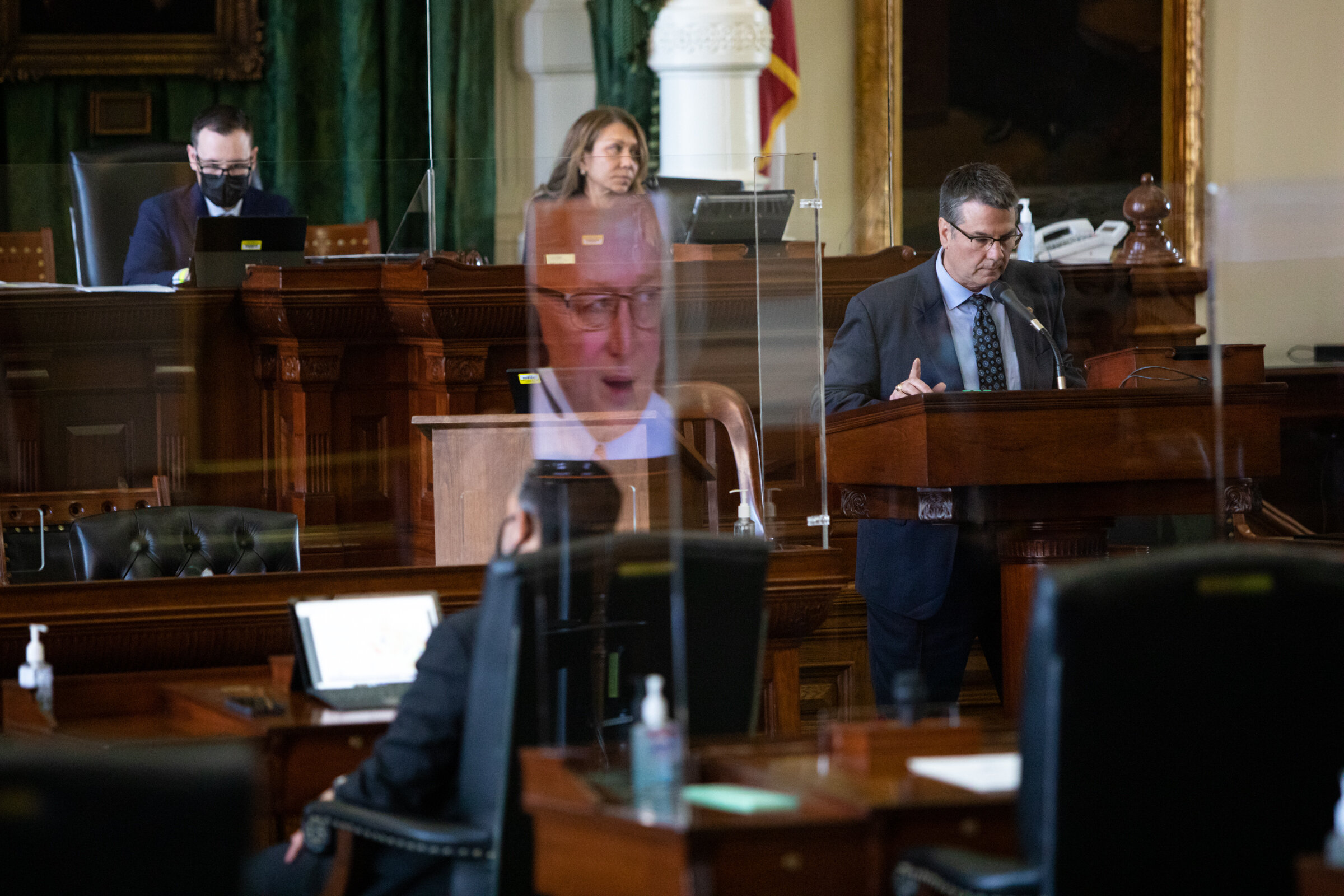

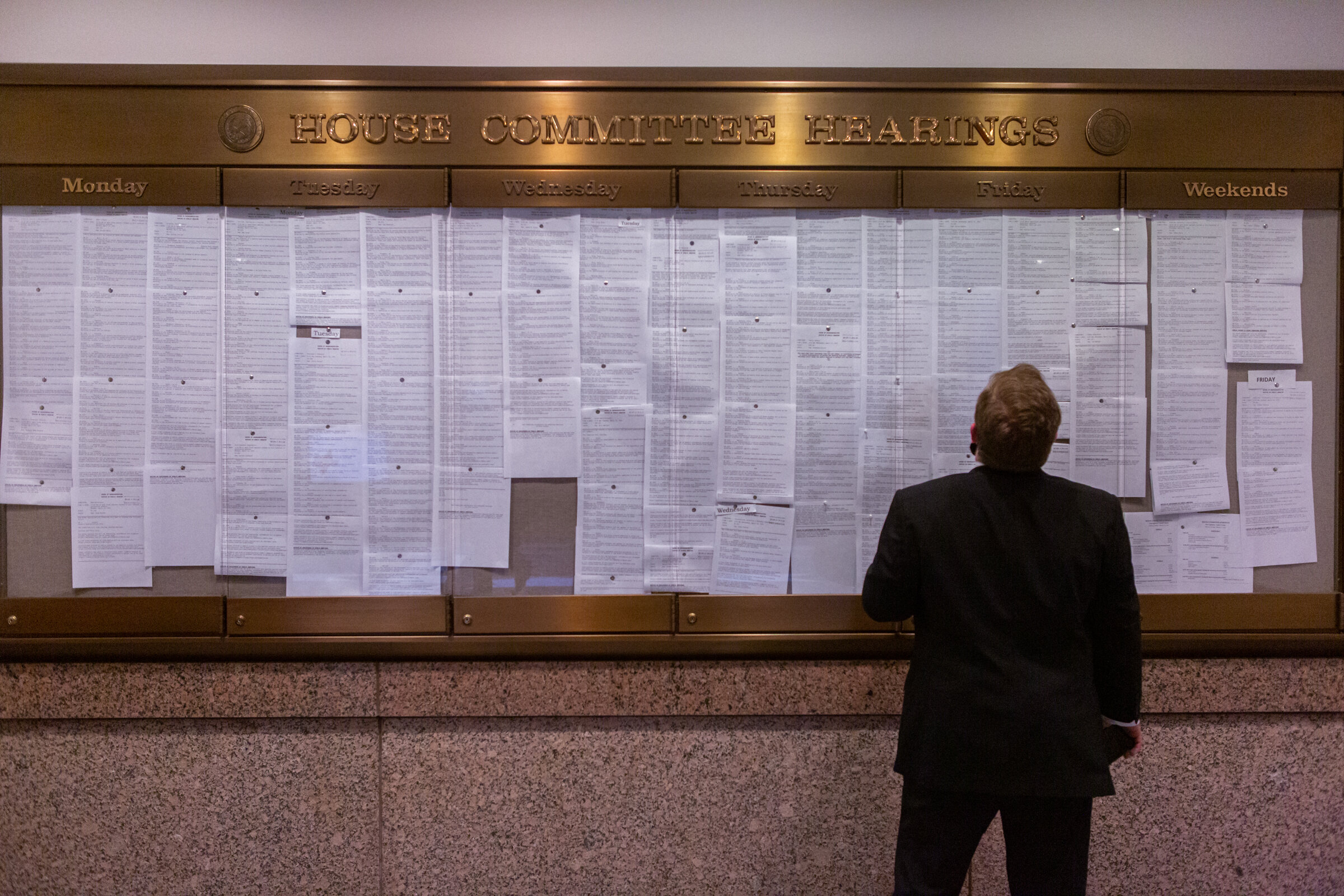

Five Months with the Texas Senate

This year started with a five-month job working as a full-time photographer for the Texas Senate. I was documenting the Senate’s 87th Legislative Session. Being in the room for committee hearings and floor debates was wildly interesting, educating, infuriating, as well as uplifting—often all within the span of a few hours or even minutes.

Texas has a unique legislative process. The state legislature only goes into session for five months every other year. And while the governor can call a special session, for the most part, all the bills that are going to be passed every two years have to go through the legislature during that five-month period.

I took the job because I thought that this session would be especially consequential as well as visually interesting because of the Black Lives Matter protests that had happened in 2020 as well as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. I couldn’t have guessed just how consequential it would become.