I, like so many people throughout the country, have been overwhelmed with emotion following the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and countless other unarmed black men and women at the hands of police. As a photographer living in Austin, when I saw that protests were scheduled in the city that has become my home I felt ready to use my skill set as a photographer to channel the anger, sadness, and pain that I was feeling into something positive.

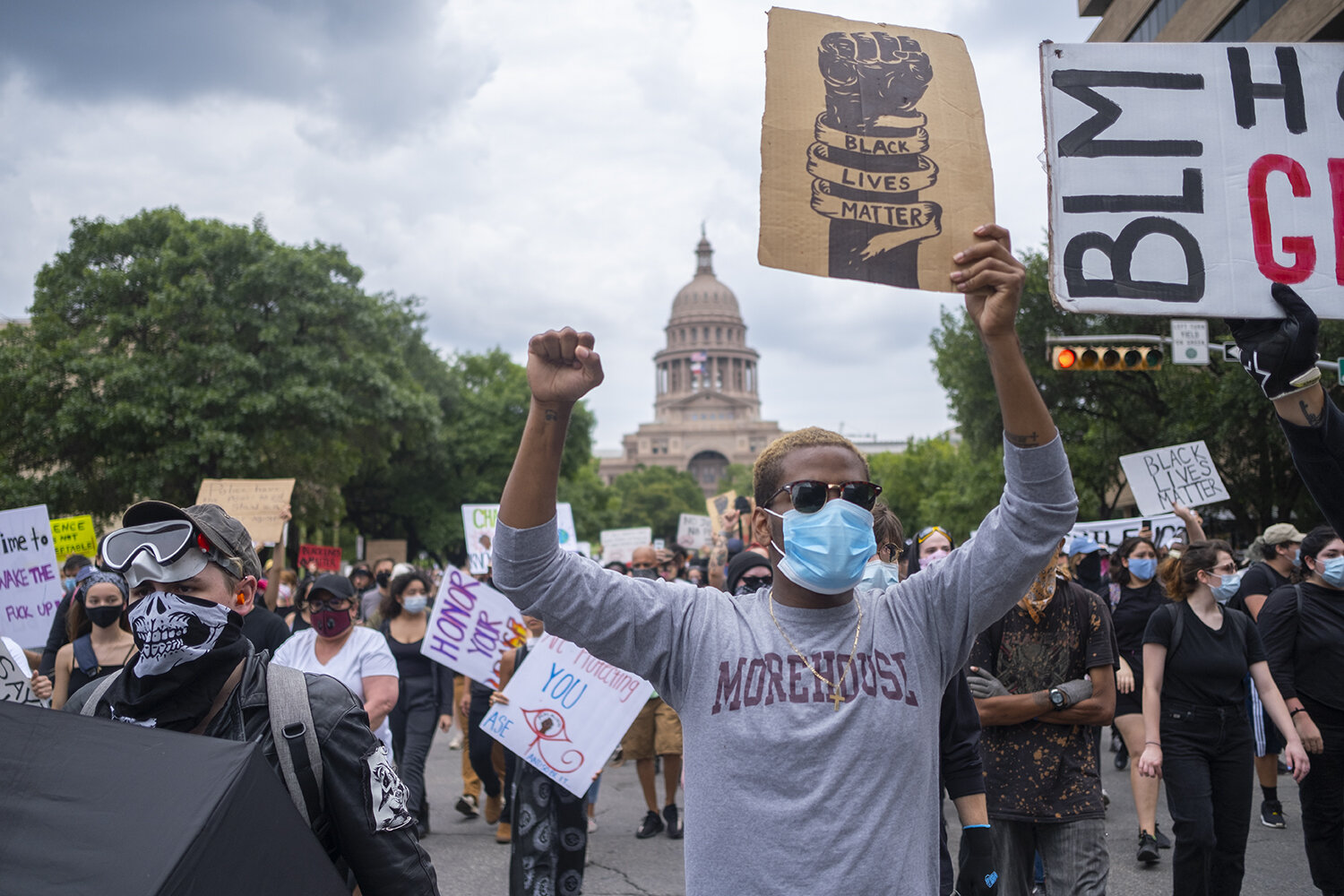

People march from the Texas Capitol building in Austin on Sunday, May 31st to protest the police killings of Mike Ramos in Austin and George Floyd in Minneapolis.

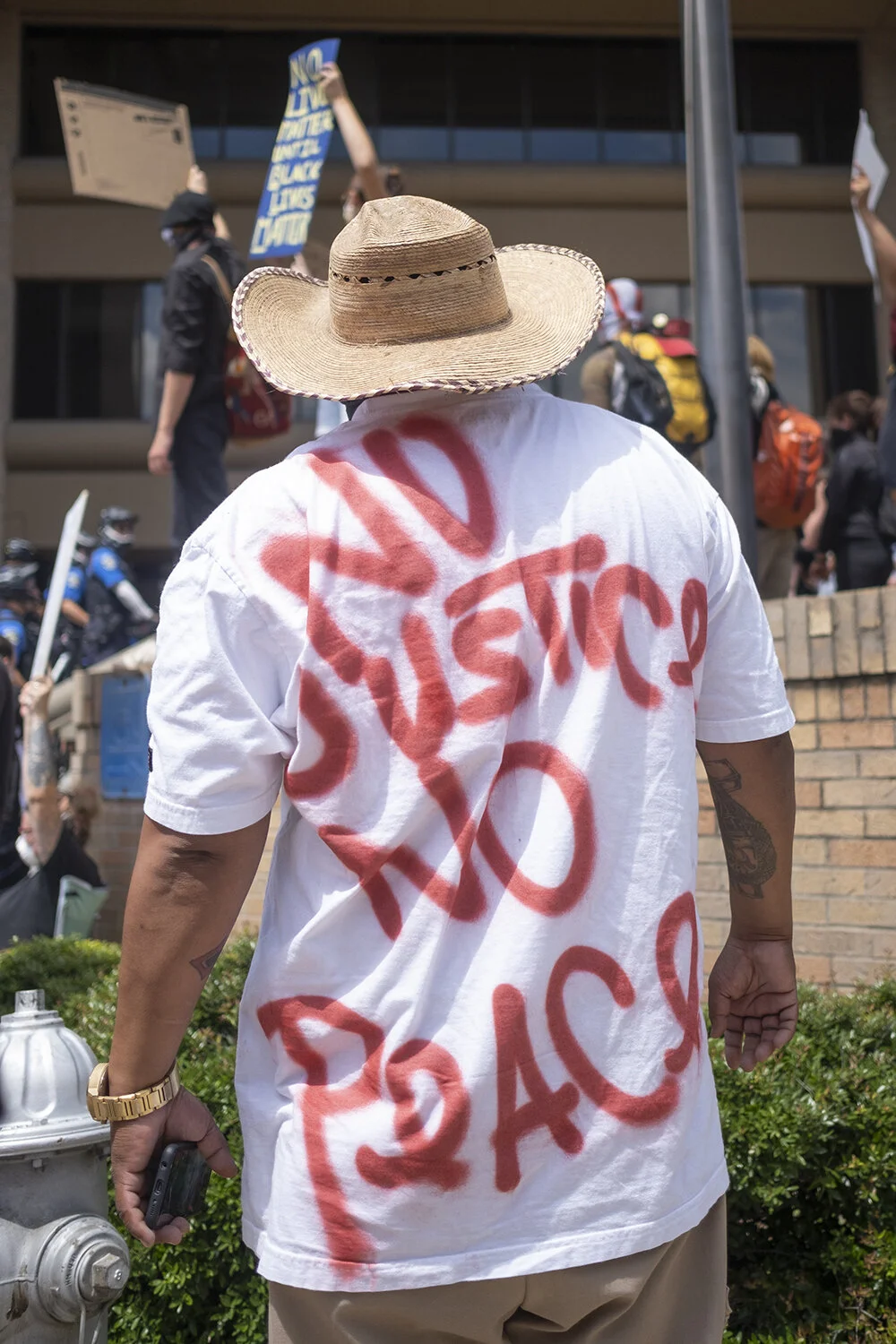

Protestors gather in front of the Austin Police Department Headquarters on Saturday, May 30th.

“When I have my camera on me, I don’t forget that I’m a black human being”

As I posted my own images and scrolled through various social media feeds, I saw a growing collection of images from protests in every major city and beyond, but also a growing conversation about responsible documentation and representation in the photojournalism community surrounding the specific events taking place.

Scrolling through Instagram, Chris Facey’s words quoted from his piece with the New Yorker reminded me of my privilege.

“When I have my camera on me, I don’t forget that I’m a black human being”

As many people posted black squares in solidarity on “Blackout Tuesday”, Andre Wagner added to Facey’s sentiment.

“I'm sorry I can't do this blackout y'all--my everyday life has a been a protest...I've been crying the past few days out of frustration of wanting to tell more photo stories of my brothers and sisters but also wrestling with the feeling like it's not safe for me to do the work I've been called to do. Since the birth of this medium, black photographers' voices have been suppressed, though I feel strongly that we need to have work by people that understand what it feels like to be in this black body.”

As a white male photographer, I have the privilege to wear my camera—even in an incredibly tense situation with police officers—without considering my race, gender, or how I will be perceived. It’s incredibly important to recognize that privilege, especially now. As David Gonzalez put it on Facebook, “Now is NOT time to handicap which foto of Black suffering will win a Pulitzer. Especially now when your POC colleagues are worried about the safety of their fam, lives and community.”

On one hand, I believe it’s important that I use my privilege as a white photographer to go out and shoot. But in doing so I have to be conscious that my work does not take precedence over Black suffering, re-traumatize communities of color, or endanger the people I am photographing especially if those people are from an already marginalized community. I must also remember that Black and other POC photographers have been historically marginalized within the photojournalism community and elevate their voices as I tell my own stories.

The Authority Collective has created this valuable document for photographers hoping to create powerful work without causing harm. It’s specifically about photographing police brutality protests, but I think a lot they bring up can be extrapolated to other types of work.

Quoted in that document, filmmaker Ligaiya Romero explains:

“As photographers/filmmakers, we need to ask ourselves, is this image sousveillance (from the bottom pointing up, holding power-holders and oppressors accountable) or are we furthering surveillance (from the top pointing down, adding to a history of violence and surveillance of Black, Indigenous, and POC bodies, and creating a document that can be used to further that violence)?”

Checking Instagram on Monday afternoon, I saw an Instagram post from Nolan Trowe:

“Are your images hurting or helping?” he asked. Thinking back, I could clearly answer that question during Saturday’s protests. I wanted to thoughtfully showcase what I was seeing which included mostly peaceful protesting with some tense moments between protesters and police. I felt that my images accurately depicted the reality I saw while ensuring the safety of the people I was photographing—I felt that my images were helpful. At the same time, asking if my images are helping or hurting as I’m shooting brings up the possibility that I could be censoring my images.

While objectivity is at the foundation of photojournalism, the Authority Collective once again explains,

“When photojournalists use objectivity as a framework to excuse dangerous practices such as identifying vulnerable protesters, they are failing to see how they benefit from a political structure that encourages "objectivity" as a mode of oppression.”

As I arrived to Austin’s City Hall on Sunday afternoon, I felt differently than I had Saturday. As the Austin Justice Coalition canceled their official protest, I saw a larger number of agitators alongside a growing number of individuals wearing the subtle suggestions of white supremacy. I did not feel compelled to document the potential conflict. I should note that I was not on assignment so I was able to make that decision.

As I left City Hall I walked by Central Christian Church. I saw a woman who introduced herself as Janet Maykus, a Senior Minister standing quietly, but with purpose in front of her church.

She explained to me, “I wanted to be a calming presence” and specifically called out the white men she had seen driving by yelling things like “Start the revolution!” and “Burn it down!” She went onto say, “It’s not our [white people’s] place to say that...In crowds, things happen...it insights anger and aggression. I don’t want anyone to be hurt, I want voices to be heard.”

Her words resonated as I reflected on how photography has the potential to both uplift or harm its subjects.

“Start the revolution! Burn it down!”

“It’s not our [white people’s] place to say that...In crowds, things happen...it insights anger and aggression. I don’t want anyone to be hurt, I want voices to be heard.”

Janet Maykus, Senior Minister at Central Christian Church

So many prestigious photography awards and the photojournalism industry in general often rewards photographers who capitalize on the pain of already marginalized communities. As members of various photography communities, we—white photographers especially—must make a more concerted effort to stop making those types of pictures especially when we are not part of the communities we are documenting.

I wouldn't expect my photos of the protests in Austin to win awards, but I've decided that as a white photographer I won't be submitting my images for any awards. I would encourage other white photographers to consider doing the same. To be clear, I only photographed the protests in Austin for less than a day and a half. I know that I am not making any real personal sacrifice by choosing not to submit my images for any awards.

Of course, the issues David Gonzalez and the Authority Collective raise don’t start with people submitting photos to win awards, but rather taking them in the first place. That being said, change can only come from within the photojournalism community if white photographers make conscious choices to relinquish the power we have and elevate marginalized voices.

I don’t expect that all white photojournalists will decide to skip submitting their images of the ongoing protests against police brutality. But what if they did? Of course Black photographers have the talent to win those awards on their own, but wouldn’t that be a powerful form of solidarity from within the photojournalism community?

- - -

A few days removed from last weekend’s events, I am seeing a lot of powerful images that reveal some of the shortcomings of my own documentation of last weekend’s events. The police did severely and even critically injure protesters, which is something I didn’t capture thoroughly.

The photos in this post wouldn’t negatively impact anyone, but did I leave out an important part of the story?

Because I wasn’t on assignment I approached the protests in a way that was more about documenting my own experience rather than capturing the news as a photojournalist. A big part of me also very simply didn’t want to get sprayed with mace or shot with sandbags—something many other photojournalists have endured in the last week.

Again this makes me think about my own privilege as a white man not directly impacted by police brutality. I recognize that reflecting on my own privilege within a specific industry feels self-indulgent to a certain extent when people’s lives are at stake. I recognize that this topic and conversation is one of many that I need to be having.

- - -

If you have any comments, responses, or criticism regarding this post or my work more broadly I’m open to hearing it all. I will continue to educate myself, consider the intentional and unintentional impacts of my work, and spark conversations with friends, acquaintances, and strangers.

I am personally making my way through this document: Resources for Photographers and Beyond on Anti-Racism. It was also compiled by the Authority Collective.

I’ll finish this post with a short list of Black photographers, artists, editors, and organizations whose work and presence on social media have shaped how I personally think about issues of representation within the photography industry. Check out their work, hire them, and buy their books and prints!

Authority Collective

Diversify Photo

Women Photograph

Alexandra Bell

Brent Lewis

Walé Oyéjidé, Esq.

Dana Scruggs

Deana Lawson

Rahim Fortune

Dawoud Bey

Montsho Jarreau Thoth

Gabriella Angotti-Jones

Radcliffe “Ruddy” Roy

Kris Graves

Ibarionex Perello

Joshua Kissi

Adrian Octavius Walker

Miranda Barnes

Chris Facey

Andre Wagner